Her brand, Obaatian – which means Grandma’s Tea in Japanese – was created only four years ago, it is the only store in Brazil dedicated to the production of specialty teas

It was to be just another article that we are used to produce at Grão Especial. But our visit to the Shimada farm in Registro, São Paulo, 180 kilometers away from the capital, was very special. You can chat for a long time with the Brazilian-Japanese descendant, Elisabete Ume Shimada, who, at the age of 87, decided to launch her special brand, Obaatian, which is in just five years an international success. “it is the best black tea produced in Brazil by far”, says the tea sommelier, Carla Saueressig, the major expert on the subject in Brazil

Her journey is a life lesson and those who have the privilege of meeting her, also have the almost religious obligation of passing her life lesson forward to as many people as possible. And that’s what we’re going to do here.

With her vitality and lucidity, she told us throughout a Saturday afternoon, her stories of entrepreneurship, overcoming, faith and optimism.

Brazil was once a major tea producer

Few people know, but, in the last century, Brazil was once a relevant producer of tea in the international market, thanks to the influence of Japanese immigrants.

There were several tea producers, which lived in the city of Registro, known as the capital of tea in Brazil.

In the 1970s, there were 40 tea factories, 1,500 producers and a production of about 10,000 tons per year in Brazil. In the 1990s, our tea quality declined, partly thanks to the euphoria of exporting tea producers. But the product quality worsened and quickly, China and India, took the space that was previously occupied by Brazil in the international market.

When the Plano Real was enacted, and the local currency reached the same price of the American Dollar in the stock market, exporting became unfeasible and, one by one, all factories closed, except Amaya, the only tea factory that remains active to this day.

The tea plantations from the region of Registro were decimated and replaced with banana and pupunha trees, among other crops.

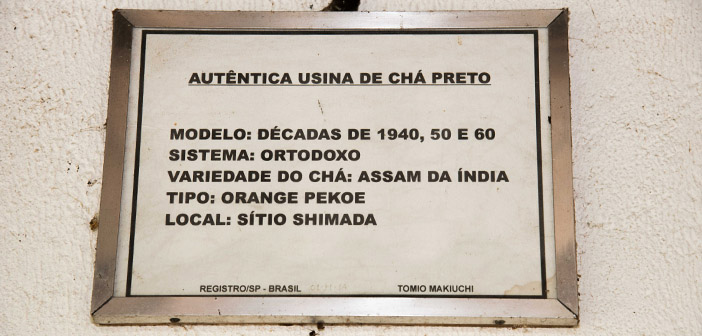

Opening plate of the factory.

Tea and the Shimada family: It all started with Dad

Ume Shimada’s father and mother arrived from Japan, specifically from Fukushima City, in 1934. According to Ume, there was no need to come, since they already worked in the silk farms. But as the Japanese government propaganda was very convincing, they decided to immigrate.

As soon as they arrived, her father was sent to the work in a coffee farm, in São Paulo’s countryside. But as he and his countrymen never had seen coffee in their lives, when they were harvesting the coffee plants, they left all the fruits and collected some leaves, following the process done with the tea.

“Their boss was very angry. But because they do not understand why he was that mad, due to the language barriers, which they that did not know at the time, this episode came to nothing. My father worked at this farm for three years”, recalls Ume.

Due to the poor work conditions, my father fled to Registro in a horse-cart, “carried by eight horses”, Ume says emphatically. And he began to plant sugarcane, making pinga (a sort of sugarcane spirit) and molasses.

One day he suffered an accident and got half-part of his body burnt. the doctors said that he would die. But a sage countryman advised him that he had to bathe in mud. “And he healed miraculously”, believes Ume.

He began to plant other things, especially coffee, but he had to give up because of the coffee borer beetle, a pest. “Dad was careful not to burn the coffee plants, he cut them off and replaced them with the camellia sinensis, the tea plant”, she says. This was around 1950, shortly after the Brazilian government donated lands to the Japanese immigrants, as part of the agreement between the two countries.

The first tea changes in Brazil came from the hands of the first Chinese immigrants.

All six children helped their father but his favorite assistant, when dealing with tea, was Ume. “My father brought a seed of tea here to the farm, where it came from I do not know, and sowed it in the land.” That tea sprouted, then he put the seedlings in cans and chose me to collect the buds of tea”, she says.

Ume’s father started the tea plantation, and thanks to the climate and temperature conditions, it was so successful that in a short period of time, the family set up a factory, called Chá Oriente. They even were capable of exporting their product.

“I remember it was very well done, every process was manual. I was responsible for packaging the tea in 100-gram packs. And my father was a hurried man, it was hard work, we had to do what he asked for quickly”, she recalls. “Then he stopped the tea business and one of my brothers took over”, she explains.

As he had experience in working with the silkworm, he called a brother who still lived in Japan to set up a silk production in Brazil. This brother came and brought all the machinery. But the business did not prosper, thanks to local corruption. “The officers were always against my father, charging fines, even when there was nothing wrong. He became very angry and closed the silk factory. They produced a beautiful fabric, I remember to this day the skirt that my mother wove for me”, remembers Ume.

Great care is taken in all stages of Obaatian tea production.

After getting married, a season on the beach

After the wedding, Ume and her husband decided to move to the south coast of São Paulo, in Itanhaém, and since she had received a sewing machine as a gift, for the five years in which lived there, her job was sewing, an activity she had learned from her older sister. “I started sewing and never missed my job. She taught sewing, too. One I had more than 11 students at a time. I even gave them a diploma”, she recalls.

To satisfy her wishes, her husband built a large house to serve as a sewing school. When it was ready, Ume thought it was no longer the ideal place to offer education to her children. “I attended a catholic school of nuns and I thought that, on the beach, everyone was almost naked. It was not good for my daughters”, she says.

Then one day, her brother asked them to go back to Registro, to take care of the farm.

After a few years, they began planting reeds to make mats and slippers and even bought a machine to make long carpets. I could produce 11 rugs a day.

“But after a while I was not very pleased. I thought: My kids are getting big now, they must study in São Paulo. In one of these coincidences of life, one day, she had gone to visit his mother and heard one of her brothers say that he was tired of working at the street market in São Paulo and that he was going to sell his tent. she ran home to tell her husband the news and ask if he would buy her brother’s tent. He accepted!

“We worked, my husband and I, five years at the street market, using an old truck that had not had brakes. I thought: I’m tired of working at the street market. Then I heard that my niece had an eyeglasses shop and that she was going to sell it.

Result: influenced by his wife, her husband bought the eyeglasses shop.

They moved to the same house where the eyeglasses shop was. “But I had to take care of the shop and do the housework. And my husband was there, watching TV. I said we had to get another service”, she says. Ume decided to pound mochi (a Japanese rice cake) and they took it to the Oriente shop, in Liberdade, to sell it. “People loved it and did not stop ordering anymore. Moti earned us a lot of money, we were able to build another house on the farm”, she recalls.

Ume came to have four mochi machines and delivered the product with a fair cart. But other Japanese and descendants also began to produce mochi, the competition grew stronger and business was no longer so profitable. But to this day, Ume’s mochi is remembered!

Soon, the husband decided to return to the farm that was leased at that time. And Ume stayed in Sao Paulo for a while. After selling all the mochi stock, she returned to the farm.

When she arrived, she found everything messy, and told her husband that she would stay only if they renovated the farm. They started by the chicken coop, then built an almost industrial kitchen. At that time, they worked on the tea harvest which was all sold to a local factory.

On a New Year’s Eve, the youngest daughter brought a different fruit and Ume loved it. On the same week, she went to the Oliveira Barros farm supplies store to see if they were selling seedlings of lychee. She bought three hundred plants.

The seller swore that in three years, lychee trees would already be bearing lots of fruits. After five years, no lychee. She called the seller and made and gave him the biggest scold ever. “You are such a liar, you said that it would bear fruits after three years. Until now, nothing. I’ll destroy everything”.

It was not necessary. In that year, the plants were loaded with lychee, the branches even fell so heavy. One of the problems was solved, Ume had now another. How was she going to sell the production? In Brazil, no one knew about lychee, originating in China. “We offered but nobody wanted to buy it. They thought it was a hard strawberry! No one cared. We decided to sell at the Vila Mariana’s traffic lights. But as nobody knew it, we ended up giving it to the people for them to taste it”, she says.

Using a box truck, they slowly started delivering it to the small supermarkets in the area, and with great effort the lychee gained popularity.

As a true pioneer, she was the first to plant lychee in the Ribeira Valley. With the success of the production, Ume had to face another problem: security. During the harvest, thieves invade the property to pick up the lychee. They need to pay a private security service day and night. “What does the government do for us?”, she asks

Despite the problems, lychee farming is a success, it is more than 20 years old and totally organic.

How she started her story with teas farming

Ume’s teas were all bought from the Amaya factory. But with the crisis, the company gave up buying its tea buds. She was devastated, she cried, she did not know what to do.

As there was no more market, they decided to stop harvesting for 12 years, enough time for the tea plantation to be covered by bushes, mainly by a type of vine that covers the plant from its root.

“My son, who lives in Rio Grande do Sul, came to visit me at the end of the year and help me harvest the lychees. He decided to visit the tea plantation and, on the way back, met with a Japanese friend, Tomiko, who asked who the owner of the tea plantation was.

From chazal, the best black teas from Brazil come out.

Tomiko was a kind of Gyro Gearloose in Registro and warned the family he had found in a junkyard in the town, two machines to roll the tea leaves, which were essential for the manufacture, but which had to be recovered.

Ume went to see the machines on the old iron and thought Tomiko was kind of crazy. They were in a bad state. She did not believe it, but her Japanese friend was always excited. “Buy it”, said Tomiko. The owner of the old iron made a discount and Ume bought the machines.

Tomiko recovered the machinery after six months of work. And while he set up the machines, the family, along with three volunteer students from schools in the area, cleaned the tea plantation with their hands, “crawling like alligators”, she recalls. “I killed two poisonous snakes myself. It was really hard to clean up the tea plants. But we left everything looking good”, she recalls.

The entire process is handmade, which begins with manual harvesting, where only the bud and the two younger leaves are selected. The result is an amber black tea with body and a smooth astringency, with honey and malt aroma and flavor that resembles fruits like lychee, peach and apricot.

Obaatian tea factory.

In November 1st, 2014, the factory was opened that was called chá preto do sítio Shimada. Only later did he become the internationally famous, Obaatian, Grandma’s Tea.

On the opening day, a friend tried the tea and proposed to help the family to market it. He took the tea to Asahi Shimbum, the main newspaper of the Japanese community outside Japan, and fourth in the country. They liked the story and did an exciting report on Obaatian tea. And the Ume’s and her tea story spread throughout the Japanese colony in several countries. And more than that: her story caught the attention of Japanese entrepreneurs who invited her in 2015 to talk about the plantation recovery was at an international event, the Japanese Black Tea Festival.

Ume returned there in 2016 and 2017 and even received a visit from Japan’s leading black tea farmer, Hirosato Goto. “He spent almost a month here and his visit was very important for us, since he taught us many things”, she says.

Today, her daughter Teresinha Shimada is responsible for the harvest, along with 10 more employees. There are 30,000 plants of camellia sinensis, organically treated and harvested manually. Ume, because of a pain in her lower limbs, can no longer participate in the harvest. But let no one doubt: she remains active throughout the rest of the process. “It is she who commands here”, says her son-in-law, Aurelino Ferreira Cruz, Leo, the family agronomist. And does anyone dare to doubt?

In addition to Teresinha, about 10 people assist in harvesting the Obaatian teas.

Shimada’s farm production is equivalent to 450 kg of tea per year, a business that must profit, by the end of 2018, an amount approximate to R$ 150 thousand. Now, they are also harvesting a small production of white teas that will soon be available in the recently opened store in Aclimação, São Paulo.

They already export to Japan, England, Canada and Ume’s biggest wish now is for Queen Elizabeth of England to have her tea at Buckingham Palace and become a fan.

The daily life

Ume keeps waking up at dawn, around 3:30 a.m., every day. “I wake up, pray and ask God to give me many years of life, because I still have many plans. I love living, can you see?” Then she does her daily gymnastics, has her coffee slowly, does some crochet and now it’s time to work. She is going to plant her seedlings, which according to her have already surpassed the mark of 17 thousand, ending a cycle that started the same way, back there, helping her father when she was still five years old.

First white Obaatian teas.

The store

In 1st of May of this year, the grandson Swan Yuki Hamazaki, considered her right arm, opened a tea store, Obaatian, Grandma’s Tea, www.obaatian.com.br next to the eyeglasses shop of the family, in the Aclimação, São Paulo, today under the direction of the other daughter.

Yuki was responsible for the design, logo and packaging of Obaatian tea. It is possible to buy packages of tea of 50 and 100 grams in the store, besides diverse accessories to prepare the beverage.

Yuki plans to sell blends of black and white teas, which are expected to be produced by tea sommelier Carla Saueressig, Brazil’s leading expert on the subject.

The Shimada and Grain Special team: guess who was the liveliest?

Photos and videos: : Clodoir de Oliveira