How two agronomists with Master’s and Doctoral degrees engage in the production of single-origin chocolates, without concessions

César Frizo and Vanessa Rizzi met in Piracicaba while still studying agronomy. When they started dating, one of the couple’s favorite hobbies was to produce with their own hands: planting sugarcane to make cachaça and wheat for homemade bread, growing grapes for wine, and whatever else they could do.

During his childhood, César spent many summers at the family beach house in São Sebastião, which coincidentally had a huge cacao tree in its garden. At 23, he assembled a small factory in his kitchen and produced his own chocolate for the first time. The results, however, were not that great.

Fazedores de Chocolate

After meeting in college, César share his experience with cocoa with Vanessa, which let them to begin researching about the plant in the college library. In 2013 and 2014, the beach cacao tree produced a lot of fruit, and they decided to establish a small factory in the garage of César’s grandmother’s house, in Guarulhos.

They began looking for machinery but could not find anything. They imported a small stone mill, with capacity for 3-5 kg, from the U.S.-based Cocotown. Following that, they bought two smaller ones – a Spectra and a Premier machine – also from the U.S. and with capacity for 3-5 kg each. Sales increased, and they decided to build their own stone mill, with capacity for 30 kg. They developed the project themselves and took it to a lathe operator to run it. They then began using a roll refiner to grind the cocoa into very small particles, which also streamlines the chocolate-making process.

The first sales of their chocolates went to the Piracicaba-based Acorssi pharmacy, which is very well-known and frequented by the staff of ESALQ (“Luiz de Queiroz” School of Agriculture), specializing in marketing compounded drug s and natural products.

A new phase in Cunha, RJ

Using only cocoa and organic sanding sugar, Raro currently produces 400 kg per month of bean-to-bar chocolate. Vanessa is responsible for the entire production process, having finished her Master’s and doctorate degrees in genetic diversity and plant breeding. “Before being a chocolatier, I am an agronomist,” emphasized Vanessa.

“I feel like an agronomist making chocolate. My biggest inspiration is chocolatier Claudio Corallo (www.claudiocorallo.com). He is my best inspiration,” said Vanessa.

That is hardly surprising – Claudio is an Italian agronomist, based in São Tomé & Príncipe, in Africa, and owner of the brand that bears his name, which produces very fine chocolates. He also handles the planting of the cacao he uses.

Recently, thanks to a professional proposal from César, they moved the factory, which is no longer that small, to Cunha, near Paraty, in the state of Rio de Janeiro. “Cunha is a tourist town, very well-known for its production of ceramics. We have many plans and are thinking of doing something for the city. On 4/4, we will be promoting a course including a visit the factory and tasting of chocolates. It has been a success, and there are no more vacancies available,” she said. At a cost of R$200.00, Vanessa intends do it on other occasions. For that, however, you should stay tuned to the website www.rarosfazedoresdechocolate.com.br.

Meanwhile, they ship their production by mail to all Brazil. In São Paulo alone, Raro’s bean-to-bar chocolates can be found in 15 addresses such as the Isso É Café coffee shop (www.isoecafe.com.br), Empório Santa Luzia (www.santaluzia.com.br), Quitanda (www.quitanda.com), Empório Chiappetta (www.chiappetta.com.br), Loja Diária (www.casa.diaria.co), and Obaatian (www.obaatian.com.br).

Raro’s chocolates

Raros only makes bean-to-bar chocolates with cocoa from different producers from Espírito Santo and Bahia. It stands out for not mixing the provenance of the grain and maintaining the origins. Currently, they have eight flavors available, all in 50-gram bars, sold for R$ 11.50. “What varies are the percentages of cocoa, which can reach up to 100%, as in our flagship product,” he said.

Chocolates da Raros

In fact, the packaging of the 100% bean-to-bar reproduces the design of a rhinoceros, making it clear that this is not a chocolate for any taste. “It is made only with one ingredient, cocoa grown in Linhares, in Espírito Santo, the only controlled denomination of origin for cocoa in Brazil. I really like the taste of cocoa there. It is a little sweeter and less acidic,” he explained.

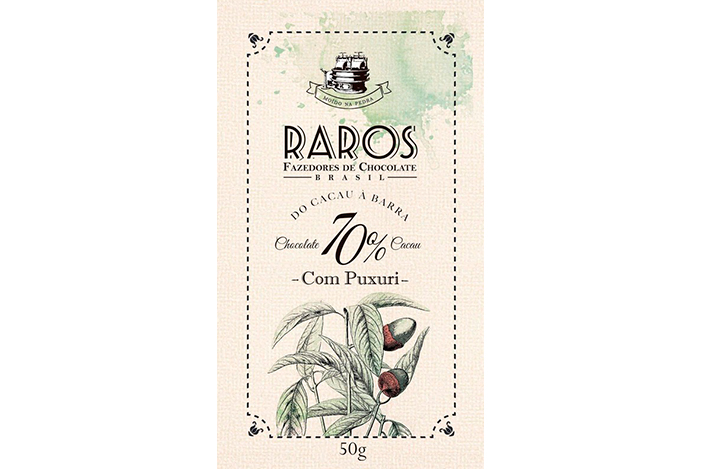

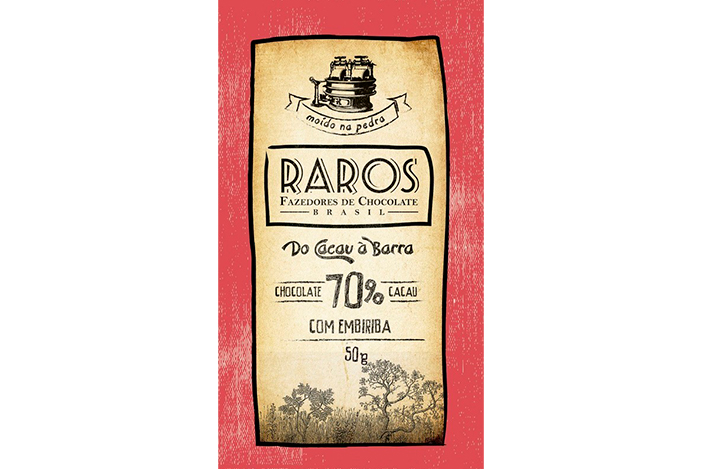

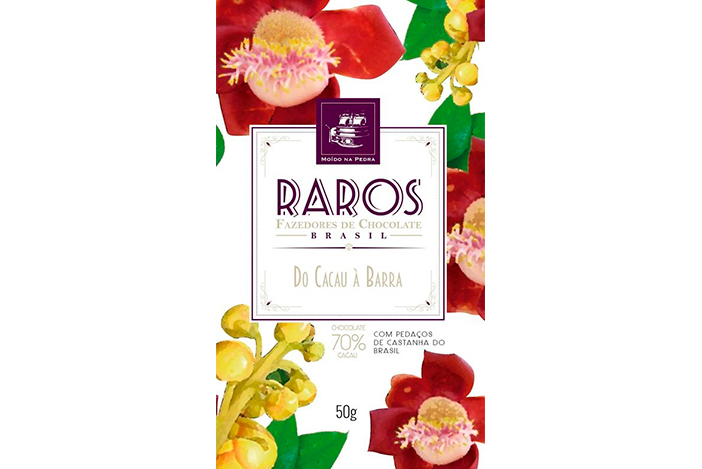

It is also possible to choose between the Linhares origin 70% chocolate, Bahia 74%, Linhares origin 65% with nibs, 65% with pieces of coffee from southern Minas Gerais (Carmo de Minas), 70% with Brazil nuts, 70% with Puxuri, and 70% with Embiriba.

Chocolates da Raros

“We found both Puxuri and Embiriba in the Lapa market, in São Paulo, while doing our research. Puxuri is a Brazilian nutmeg, with a large, dry seed. Embiriba, in turn, is reminiscent of pepper. I had never heard of any of them, but I took them to the factory to try them out and noticed that they combined beautifully with our chocolates,” she said.

In addition to settling in the new city, they intend to explore new origins and make different combinations. “Preferably, we wish continue with our research and discover other Brazilian products that are little known to us, and mix them with our chocolates,” she explained.

Chocolates da Raros

Cocoa production

About two years ago, the couple bought a small farm in São Sebastião, on the north coast of São Paulo. Called São Francisco, it has a hectare and a half in area and had been abandoned. There, they found some cacao saplings, which they intend to use mainly for their research.

Cacau

“Because of the witch’s broom in Bahia, Brazil has lost much of the plant’s genetic diversity. We do not know what kind of cacao we have on the site, so we need to do some research. We lost the genetic wealth of cocoa when so many saplings were burned. The way it was planted, on a large scale, as a monoculture, enabled the easy spreading of diseases. We wish to rebuild its genetic history and, who knows, help discover new species,” she said.