The goal is to be among the top 16 baristas in the world

Brazilian champion Barista 2017, Leo Moço, has a career full of successes. He won the same competition in 2015, and lives a busy life, due to his cafeteria, Café do Moço, in Curitiba, his roast works, and of course, the care of his family.

In November, he will travel to Seoul, Korea, to attend the World Barista Championship, to be held November 9-12th. A tough challenge. It is dominated by the young oriental baristas who, as Leo himself explains, are mostly financed by large companies, very young (around 25 years old), and they train for more than one year to attend the event.

So different from our reality. Abroad, the event calendars are defined with more than a year in advance, which you can plan and prepare for. “In Japan, just to get a glimpse, the barista trains the coffee roast profile that it will present throughout the year”, explains the Brazilian champion. “In fact, they have already defined the champion that will defend the country in the 2018 world barista championship”, he says.

(Leo with the title of Brazilian barista champion, the third won by him /Photo: Facebook BSCA)

In Brazil, the championships are scheduled in the last hour and usually, the attending baristas know their coffees that they will work with a week before the championship happens.

Another problem – that Leo described – is that the espresso machine used in the world championship is a Victoria Arduino, Black Eagle model, with a vaporization and extraction system, and the one used in the Brazilian championship is another machine totally different. “The sizes are different, the positioning on the bench is different and the structure of my presentation has to change”, Moço explains.

The Japanese Coach

This year, Leo decided to dive right into the International Championship. He hired the Japanese coach, Yoshihara Sakamoto, which hails from the city of Yokohama. He is the current coach of world’s vice champion, Yoshihazu Iwaze.

But it takes a lot of money. Only the coach costs him US$ 2,000 per day, plus the airfare, hotel and food. Meanwhile, Leo Moço’s travel, accommodation and food costs in Seoul will be paid by BSCA. “I have trained for three months, they train for more than a year”, he says.

In addition to all these high costs, they have one more obstacle: the overwhelming majority of competitors, most of them use the Gueisha coffees from Panama, the most expensive in the world. “The vice-champion from Japan used a Gueisha coffee costing US$ 5,000 per kilo. And he was no exception: in the last Japanese championship, of the six baristas who were participating in the final, everyone used the Gueisha variety”, he says bemused. “Moreover, they are perfect, precise, every movement is studied and repeated to exhaustion. So different is the level that, to be very sincere, in the final of the Japanese championship this year, of the 16 finalists, everyone, without exception, could win the last Brazilian championship and certainly would’ve won it, “says Leo.

(Leo Moço preparing his espresso for competition: main Brazilian name in barista /Photo: Facebook Café do Moço)

With all these obstacles, it was predictable that the participation of Brazilian baristas in the world championship was rather disappointing. Unfortunately, it’s not because we are the biggest coffee producers in the world that we have the best baristas. On the contrary. Here, when a barista succeeds in some way, he immediately stops extracting the coffee in his daily life. You’re going to do other things. Abroad, the barista can have a coffee shop and perform a thousand different activities, such as giving lectures, teaching classes, roast and so on. But he’s always working with his espresso machine and is also always training.

How to face such competition?

In order to face the baristas that will compete in the world championship, Leo chose to emphasize our Brazilian features. “I will emphasize the aromas and tastes very typical in Brazil. I chose a special Brazilian wild coffee, a wild coffee, as the market likes to call it”, he says. It is from the fazenda Santuário Sul, from Carmo de Minas, Minas Gerais. The farmers discovered this coffee two years ago, in an enclosed forest that is part of the farm. Free from any human action, planted about a hundred years ago, this coffee plant is more than 15 meters high. “I tasted this coffee with the head judge of the Brazilian championship, Yoshi Kato, and he was very excited, because he is very reminiscent of the Gueisha coffees. It is an Arabica, but its variety is unknown. It was probably planted by some escaping slave, from some quilombo of the region, who planted it inside the forest for his own consumption”, says Leo.

In his presentation, he will praise the work of small Brazilian producers, and show their importance in the specialty coffees international market. “I want to show the world the non-human interference in the process, remembering that nature still commands, when it comes to coffee cultivation. And, to illustrate that less productive varieties bring a unique complexity to the drink. Our thinking is always of increasing the production. We need to enter the super specialty coffees market”, emphasizes Leo.

He chose this wild coffee for his espresso and, for his presentation of coffee with milk, Leo will use a coffee from fazenda Daterra, from Cerrado Mineiro, located in the city of Patrocínio, MG. A Laurina variety coffee that is a naturally decaffeinated, with 0.3% caffeine. To understand this, the arabica variety has 1.2% caffeine, without suffering any chemical process.

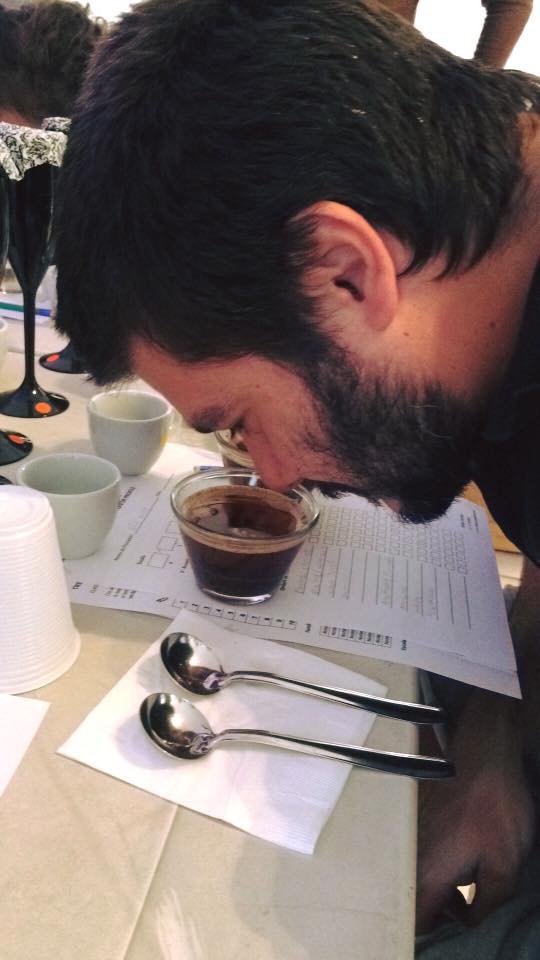

(Leo doing cupping: his presentation will extol the work of small Brazilian producers, and its importance in the global market for specialty coffees /Photo: Facebook Café do Moço)

Leo will compose his natural decaffeinated coffee milk to add high biological value, presenting a greater absorption of calcium. “The world consumes a lot of milk. I presented this idea to the coach, who helped me to get my ideas straight. As I have a background in nutrition, I want to draw my presentation to this healthy food scenario, show how the consumption of coffee is good for health by presenting this naturally decaffeinated coffee mixed with milk and red fruits like strawberry, bringing a greater absorption of calcium by the body. Everything to balance the flavors”, he explains.

In fact, the natural decaffeinated coffee is a variety which is rarely produced in Brazil. It is a mutation of a bourbon, with smaller, pointed, very different grains. Its productivity is small but it is a coffee drinking up 90 points. “IAC has done a lot of research on it, but the farms have not yet been convinced to plant it because it is a difficult variety to produce and quite susceptible to pests”, explains the professional.

“But I think it’s worth it. Last year, fazenda Daterra sold a batch of carbonic maceration coffee costing R$ 26,000 for the Spanish company Mar & Terra”, he says.

As for the signature drink, Leo sought inspiration from the wild Brazil: in the Amazon. He went to Manaus to do some research of flavor since the jungle is a full of aromas, flavors, fruits, with an unparalleled diversity of products. And chose some ingredients such as cupuaçu, pitomba, cumaru (the Amazonian vanilla), and the priprioca.

“My drink will have two layers, the first is a cold and creamy base of cupuaçu. And in the hot layer, the jurors will be able to feel the acidity of the Amazonian ingredients of different textures. I will also use a smoker very used in molecular gastronomy to smoke the cup with puxuri (a kind of nut). In conclusion, the presentation will be very cool, very Brazilian”, he rejoices.

His coffees will be roasted in Japan as part of the coach’s job. He looked for the best professionals in each area, so I do not have to worry about anything, just the presentation, he says.

How to judge what is not known?

To help the jurors work, Leo will use a model, whose main objective is to help the jurors to identify the history of the Brazilian wild coffee and also to identify the Amazonian fruit flavors, since most of them are not familiar to our palates, imagine how unusual it will be to an international panel of judges. “We bought the accessories in Japan but the model is being prepared here”, he says. “It’s very cool, because we’re also helping these professionals to recognize new Brazilian flavors”, he says.

(Leo will use a model to help the jurors identify the history of Brazilian wild coffee /Photo: Facebook Café do Moço)

“In this training process with my Japanese coach, I learned that Orientals, when they want to do something, they put a lot of effort into it, give their best. In some cultures, such as ours, this is not seen with good eyes as it should. It seems like it’s ugly to be a winner, to compete, to be the best. Here, people say: ah, the guy has to be humble. But in a competition, there is no such modesty. I want to win. Modesty has to appear in other moments: in dealing with people on a daily basis, in our personal life, not in a competition”, he concludes.

We understand you, Leo. We’re hoping you have a good result in the world championship!

When coming back

When coming back to Brazil, Leo promised to replicate his coffees at his establishment. If he separates a space in his schedule, we will publish a video presenting his recipes. Wait for it!

Before that, Leo will have another challenge ahead: he will take over his partner’s store in Manaus, “Como em Casa”, which is moving to a new and bigger address. “It will be a small Café do Moço store, a coffee boutique and roasting business, where we will sell products and accessories in the neighborhood of Adrianópolis”, he confided.

Definitely, the north of the country is already on the radar of everyone working with specialty coffees in Brazil. “Our goal is to educate the local public more and more, it is to show, mainly for foreign visitors, the nuances of flavor of our specialty coffees”, he points out.