An IBGE survey proves that there are no blacks or browns who own large farms. On the other hand, they are the majority in small family farms.

The last IBGE Agro Census (Brazilian Institute of Geography and Statistics) carried out between 2017 and 2018 and concluded only at the end of last year, shows that Brazil has five million agricultural establishments, and 45.4% are run by white producers. Brown producers have 44.5%, while 8.4% are owned by blacks, 1.1% by indigenous and 0.6% by yellow. There are 2.2 million white producers and 2.6 million black and brown ones, considering the sum of all types of agricultural properties, regardless of the culture and the size of the land.

In large properties, there are almost no black producers. Of the 1,559 farms with more than 10,000 hectares, for example, 1,232 are run by whites, 270 by browns and only 25 by blacks. The ratio is four white producers to one black or brown producer. As for small properties, with fewer than five hectares, the reality is reversed: blacks and browns are the majority.

When considering the extent of the properties of each ethnic group, the survey portrays a great inequality: white producers occupy 208 million hectares, or 59.4% of the total area of establishments, while blacks and browns have, together, less than half of that, that is, 99 million hectares or 28%.

The distortion is even more profound than the distribution of national income found in the Continuous National Household Sample Survey (Continuous Pnad) in 2015, according to which whites hold 59% of the country’s wealth, while browns hold 33% and blacks 7%.

The greatest presence of blacks among rural landowners occurs in Bahia, with 15.7%, followed by Amapá, with 14.6%. In Rio Grande do Norte is the highest percentage of brown producers, with 49.4%, as well as in Roraima. In the South region, we have the highest percentage of white producers, that is over 90%, followed by São Paulo, with 80%.

The inclusion of race in the agrarian question was an old demand and followed the guidelines already used by IBGE in population censuses. Each interviewee declared their color, choosing from the five classifications offered: white, black, brown, yellow or indigenous.

Quilombola

According to the Brazilian government, there are 3,447 quilombola communities spread over Brazilian territory, living and active, mostly formed by small black rural producers who, in addition to all the difficulties inherent in the agricultural activity of a small property, still have to deal with racism. Unfortunately, the Agro Census does not have a specific coffee culture record.

In the USA, the distortion is even more severe

With a slave past like the Brazilian, the same distortion appears in American agriculture. White American producers own 96% of the arable land. Meanwhile, the four minority groups, blacks, American Indians, Asians and Hispanics own 25 million acres, worth an estimated $ 44 billion. A century after the end of slavery, black American farmers tend to be tenants rather than landowners. Black owners are more concentrated in the southern states, from the east coast of Texas to the Black Belt (it is a serpent-shaped geographical area in the southwestern US, made up of Mississippi, North Carolina, South Carolina, Tennessee , Texas and Virginia). Most of them plant soybeans or reforestation wood. American data is from the USDA’s Agricultural Economics and Land Ownership Survey.

Specialty Coffee

Phyllis Johnson is an African American whose widowed mother worked on a cotton farm in Arkansas, in order to support her seven children, who studied and graduated. Phyllis majored in science at the University of Arkansas, majored in public administration at Harvard and founded, along with her husband, BD Imports, a specialty coffee roaster, carefully selected from around the world.

She is also the founder and director of the NGO Coffee Coalition for Racial Equity. In 2018, Phyllis Jonhson an article named “strong black coffee: why aren’t African-Americans more prominent in the coffee industry”?, which helped to raise awareness of the coffee industry around the topic.

After working with specialty coffee producers in Africa, Asia and Central America, Brazil entered its radar. When it began to interact with interlocutors of the special coffee industry in Brazil, it realized that none of them in the entire long coffee chain was black. “What? Where are the coffee producers who are descendants of Africans in Brazil?”, she asked her Brazilian contacts insistently! Nobody knew!

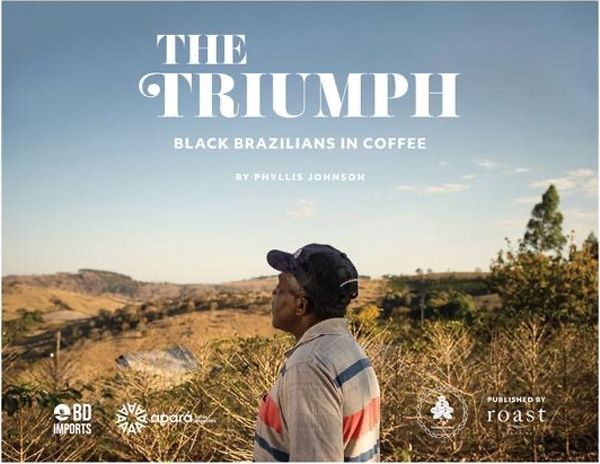

Aware of the historical similarities of the two countries of past slavery, USA and Brazil, Phyllis wanted to know a little more about the role of blacks in the Brazilian coffee industry, studied foreign and national authors and ended up writing a book, released on November 9, in the USA, entitled “The Triumph: Black Brazilians in Coffee”, for now available only in English, at Amazon and her company’s website, BDImports (www.bdimports.com).

Read the following exclusive interview that Phyllis Johnson gave to Grão Especial:

Grão Especial – the specialty coffee industry is so vast; you have visited virtually the entire world looking for the best coffees in the world for your business. Why were you interested in the history of Brazilian slaves?

Phyllis Johnson – that’s an outstanding question. I left Arkansas and I knew that I didn’t want to deal with anything that had to do with country life. I saw my mom work hard along her journey. I saw my father die. I saw my mother working with her hands and having them resemble a man’s hands. I didn’t want that for my life. She didn’t want that for my life either. She encouraged all of her seven children to study and graduate. We did it. After I graduated and worked as a scientist, I realized that something was missing. I started looking around, trying to notice something that would fill me. So I started working with coffee, something that I fell in love with. And it had to do with my own background. People on a farm. When you are a coffee importer, producing regions may be similar, but countries are not the same. Each has their own history. I was working a lot with countries in East Africa, buying coffees from Kenya, Ethiopia, Tanzania, Rwanda, where the best specialty coffees are produced. Then I started buying coffee from Central America, Costa Rica, El Salvador, Guatemala, and it was much easier.

I never thought of working with Brazil and here’s why: Brazil is huge, it is the biggest coffee producer, it supplies the world with its commodity coffee. And American buyers are not interested in paying better for this type of product. Besides, the competition is huge within the American market. There was no reason for me to work with Brazilian coffees, as my niche is different.

Then I met my friend Josiane Cotrim who wanted to start working with the NGO Women International Alliance Coffee, creating the Brazilian chapter. I had created the East Africa chapter. Josiane wanted to hold my attention and she said to me: we have black workers in the coffee fields. Come over here and see it with your eyes.

So, in 2014, I started asking my business partners about where the black Brazilian coffee professionals were. Nobody knew how to answer me. I continued my journey waiting for someone to introduce me to one of them. Nothing happened. I traveled, gave lectures, worked with big producers, with small and nothing ones. No clue! On the other hand, something encouraged me because nobody said, “stop your search, you are wrong, as there is nothing strange about it.”

One day, I was in Africa, in a meeting with an executive director of an association of specialty coffees and I asked: “When you go to Brazil do you meet with black Brazilians?” And he, as an African, answered me: “Why would I do that? They are all truck drivers.” Then, I realized that we, people descending from Africans, did not know our history. They had given me the chance to give a lecture at the African specialty coffee association, in a conference in February 2019. And I started talking about the Africans who left the continent to work as slaves in Brazil, to work mainly in coffee plantations. And nobody in the audience knew about that.

There was a person watching, from the Tanzania Coffee Board, who said he never knew that Africans had been enslaved and brought to Brazil. I was very indignant. Because the Africans who went to Brazil were mostly from East Africa, that is, from the other African side. And I was very sad. Because I am an African American descendant and I know where I came from. And this is not just about history, but about how we live and are treated today. I am one of those descendants, but it turns out that my family ended up in the USA, at a cotton farm. The only difference is that it was cotton, not coffee. I needed to do something.

Another Brazilian friend of mine, Miriam Aguiar, from the Cachoeira farm, in Santo Antônio do Amparo, was interested in the subject, did some research, and at her own farm there was a small community of black workers who helped with the harvest. Until I finally went to Brazil to meet them.

“At first, I didn’t talk about skin color; we just talked about coffee. Suddenly, they started talking about their families, their traditions, their work in the field, their good memories. The next day, we had a new event and they told me that when they saw me getting out of the car, they realized that they were no longer invisible and that their life mattered. They were so happy and proud of the importance of their work that I decided to tell the story of these people a little bit. And that was how the idea for the book I just launched emerged. They deserved it.

Grão Especial – What does this book mean for the recognition of the importance of black Brazilians to develop the coffee culture?

Phyllis Johnson – I think this is the first step and I also intend to get involved a little more with the work of quilombolas that produce specialty coffee, mainly in Bahia.

Grão Especial – Tell us a little about the book named The Triumph, Black Brazilians in Coffee.

Phyllis Johnson – In short, the book tells the stories and struggles of two Afro-descendants’ families, whose past is intertwined with the culture of coffee in Brazil, when the first slaves arrived and were taken to work at coffee farms.

Grão Especial – Which are the next steps?

Phyllis Jonhson – The next step is to work for the NGO Coffee Coalition. I’m in the land of Martin Luther King, I have to do something, but with the weapons I have, with my writing and buying specialty coffees. Each one uses the weapons they have. Most people do nothing because their work would represent very little. But if everyone does just a little bit, we will be able to eradicate racism. All proceeds from the sale of the book will go to the NGO Coffee Coalition for Racial Equity and the two families portrayed in the book.